Thinking About Scale in Land Information Systems

(BY MALCOLM CHILDRESS, KEVIN BARTHEL, AND CHRISTOPHER BARLOW)

This week in Washington, D.C., the World Bank is hosting its Annual Conference on Land and Poverty, a professional meeting that has swelled considerably in the past five years. Attendee numbers have expanded to a downright packed 1,200 people from governments, development agencies, academia, nongovernmental organizations and technology firms.

This year’s conference theme is, “Scaling up responsible land governance.” Earlier this month the Land Alliance — with support from Thomson Reuters and input from many industry partners — published a new paper titled “Reframing Investments in Land Information Systems for Land Administration.”

After years of research and practice, this paper squarely examines this year’s conference theme: scale. In response to this thematic focus, we ask land practitioners to reflect on three of the conclusions of this paper and look for opportunities to include these conclusions in our daily work related to land information systems technology.

First, incentive structures for property owners and other stakeholders should be designed to maximize participation in the formal land registry and land administration system. We have seen time and time again, from one country to the next, that there is great demand for transparent and efficient services with affordable and clear fee structures.

Take the city of Cape Town, South Africa as an example of incentives. Ten years ago the city invested in improving their property and valuation methods and procedures. Cape Town, rather than taxing households with low valuations, instead created public service-based incentives, namely access to water utility services, to attract property owners into the formal land administration process.

Research points out that a well incentivized system can lead to increased government revenues for the government agencies administering land information. This allows for responsible scaling of land governance and improvement of services.

Too often we have seen in government offices computers stacked clumsily in hallways covered in dust or piled in the back-lot as a project design failed to account for the continual financial support and upkeep needed to sustain operations. Forward planning so that capacity and technical systems are properly funded to support the growth imperatives for these governments is absolutely necessary to sustain success. It is not only a matter of implementation cost, but rather the total cost of ownership for systems.

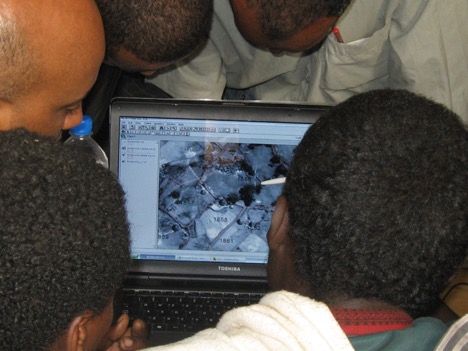

Second, just as we have a continuum of land rights, there is a continuum of technology linked to a continuum of purposes for LIS investments. The principle of Fit for Purpose importantly requires that a government or an organization that manages land information actually knows what they need. What needs to be achieved with technology, not only today but also for future purposes? A technical tool used to quickly document, map and inventory land rights may not effectively scale to manage more complex land administration needs, such as subdividing a property, transferring a property or registering a mortgage. Or it may not scale so that information can be shared with other government institutions — for instance to trigger a valuation office so that they are aware that a property was newly registered and therefore should be added to a tax roll and regular value reassessed.

Deploying technology not suited for long-term purposes poses a risk to scaling land governance. We have seen cases in which terabytes of data were collected on millions of properties’ owners to systematically constitute a living registry on the fabric of ownership, only later to slowly decay into an ever less valuable and reliable set of information as processes and systems could not scale to accommodate the continually changing relationships to land.

Third, this paper calls for new thinking about new technologies to scale land governance. Inexpensive drones, mobile devices such as GPS-enabled phones, more immediate higher accuracy imagery libraries, cloud computer and mashed-up big data, such as with global commodities information and crowd sourced maps — as examples, are all radically changing our world. Some professions are eroding. Other professions will morph and develop. A recent study by International Development Corp. estimates world data will increase 50 times by 2020.

In a short 10 years the majority of people’s land rights across the globe should be accurately mapped geographically, recorded and managed. However, this will require smart and open thinking as to how to harness new technologies and information created.

For more on scaling land governance, we encourage you to read the new Land Alliance paper authored by Dr. Jolyne Sanjak. In the meanwhile, we — together with 1,200 colleagues at the World Bank land and poverty conference — will continue to look for improved ways to scale responsible land governance.