Drones for Land Rights

BY KEVIN BARTHEL

Of all the uses for Unmanned Aerial Vehicles — popularly known as UAVs or drones — their application for acquiring aerial imagery and geospatial data for use in securing land rights in the developing world may be one of the most valuable and lasting. UAVs hold the promise to help solve the developing world’s land rights problem, monitor logging and mining for both production and compliance, and give local people an affordable, accessible tool for securing their land rights and managing their natural and cultural resources.

Coupled with a new wave of support from governments, corporations and donors to recognize land rights which lack formal documentation based on georeferenced maps, UAV technology offers hope that the world can change the paradigm of land governance in the developing world from one of insecurity, conflict and mismanagement to a “triple win” of prosperous local livelihoods, productive resource use and environmental sustainability.

The land rights agenda is both big and challenging. It is estimated that 90% of land in Africa has undocumented ownership, and 75% of land rights worldwide are undocumented. In Latin America, many urban parcels of land and much of the resource rights in rural areas, in particular the agricultural frontier, are undocumented.

For example, even though legal frameworks provide for local communities to obtain legal land title, the resource rights of the Amazon Basin are largely undocumented. In Asia, much land remains undocumented, particularly in Indonesia. The insecure land rights situation in the developing world is blamed for holding back sustainable development by fostering insecurity and under-investment, permitting corrupt land grabs and human rights violations, environmental mismanagement and deforestation, and urban slums to proliferate.

The development community is painfully aware of the global land rights problem, and the race to develop a land governance toolbox which works for local communities, protects the environment and gives business the confidence to invest is in full stride. Timely, affordable and accessible solutions for mapping parcel boundaries has been a problematic part of this toolbox.

So far, detailed boundary surveys have either relied on labor-intensive fieldwork on the ground by teams of surveyors, or expensive traditional aerial photography from conventional aircraft equipped with specialized cameras. The expense and inaccessibility of the technology has put accurate and government- acceptable land surveying beyond the means of most communities in the developing world, and also beyond the means of most local governments. National governments may be able to mobilize the resources for mapping, often from donors, but coverage is often sparse, especially in remote rural and forested areas, or not timely in rapidly changing peri-urban areas.

UAVs change this by adding an important new tool into the land governance toolbox. UAVs enable the acquisition of high-resolution and accurate digital aerial imagery to be taken ‘when and where needed’, for a fraction of the cost. This imagery can be processed and validated immediately, directly in the local community on a laptop. Land Alliance, working with geospatial data partners in Peru, has demonstrated that the Trimble UX5 fixed wing UAV platform can produce high-quality images which meet all the national survey standards and can be used to produce fully usable orthophotos (i.e., aerial photographs corrected for geometric distortions which can be used for accurate measurements) in local settings within hours. We plan to use these images in a new phase of work with communities and local government to directly assist rural landholders to formalize their land rights.

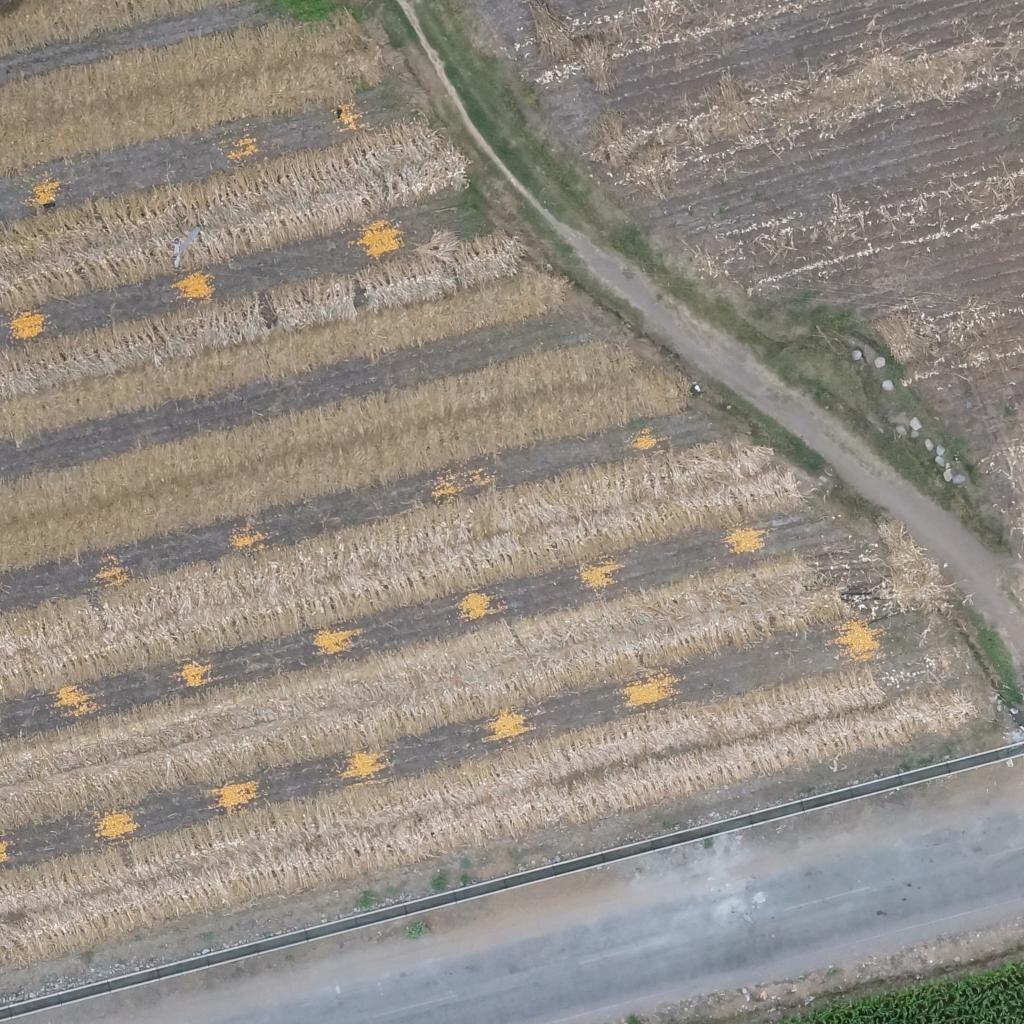

The immediacy and accessibility of UAV aerial imagery also makes it much easier to mobilize community participation in the mapping and land regularization process. In northern Ghana, one successful test involved local people marking their property corners with paper plates the children had painted at school. In Peru, farmers marked the boundaries of their plots with lime. These processes make the mapping a participatory activity led by the community, and the markers make the boundaries of their parcel of land readily visible on the imagery and allow accurate measurement to 15 to 20 cm. Information about ownership and land use can be recorded and captured in the same exercise as the aerial imagery and stored in a digital GIS database. This further drives down costs, helps to avoid errors and resolve disputes, and helps improve the quality of the final geospatial and land tenure data.

UAVs are not a panacea — like other aerial and satellite imagery, its usefulness for boundary mapping is limited in areas of heavy tree cover where parcel boundaries can’t be seen from the air. Also, flight time is limited to battery power, so at this point in development of the technology, UAVs cannot be used to map or monitor vast areas the way satellite imagery or traditional aerial photography can. It is still a new technology mostly in testing and piloting stages and is yet to be proven for many applications.

The technology is so new that most governments do not have specific regulations. Regulating UAV use is a sensitive area with a host of concerns about privacy, security and public safety. Our testing so far indicates that these concerns can be managed in the context of property mapping by engaging the full range of local stakeholders and introducing strict protocols for managing the flights.

Empowering locals

The Land Alliance intends to put this technology in the hands of local communities worldwide to quickly and accurately record the location and boundaries of their lands, and provide a powerful tool for its management. Of course, technology is not the only element to move the needle on the land rights problem. Local communities need the protection of a legal framework and rule of law, and social processes of resolving conflict. Women’s rights and rights of vulnerable groups need to be specifically documented and protected. A new wave of organizations are working on these issues — the Rights and Resources Initiative in forests, Namati in legal support, Landesa on legal frameworks, and they are influencing the global terms of the land governance paradigm through governmental commitments like those of the Voluntary

Guidelines for the Governance of the Tenure of Land, Forests and Fisheries, and through corporate commitments to better land governance, like the soy moratorium in Brazil and the zero deforestation commitments of the palm industry. UAVs can help resolve a major bottleneck in this process if combined with the development of applications, appropriate regulation, and acceptance by the official institutions of locally-led land rights regularization.

We are entering the age of the UAV. While the world debates their use in surveillance, law enforcement, package delivery, and warfare, it is already clear that they can help change the paradigm of geospatial data collection to support land rights delivery from a top-down process, to an affordable, participatory, bottom-up process. UAVs put an appropriate, fit-forpurpose tool into the hands of local people and provides the detail and accuracy of traditional methods at a fraction of the time and cost.

By using ‘drones’ for peaceful purposes, the Land Alliance is optimistic that one of their biggest impacts may be helping to solve the world’s land rights problem.